Seabed mining poses dangers to the Pacific: Report

By Andrina Elvira Burkhart

•

04 February 2026, 9:00AM

By Andrina Elvira Burkhart

•

04 February 2026, 9:00AM

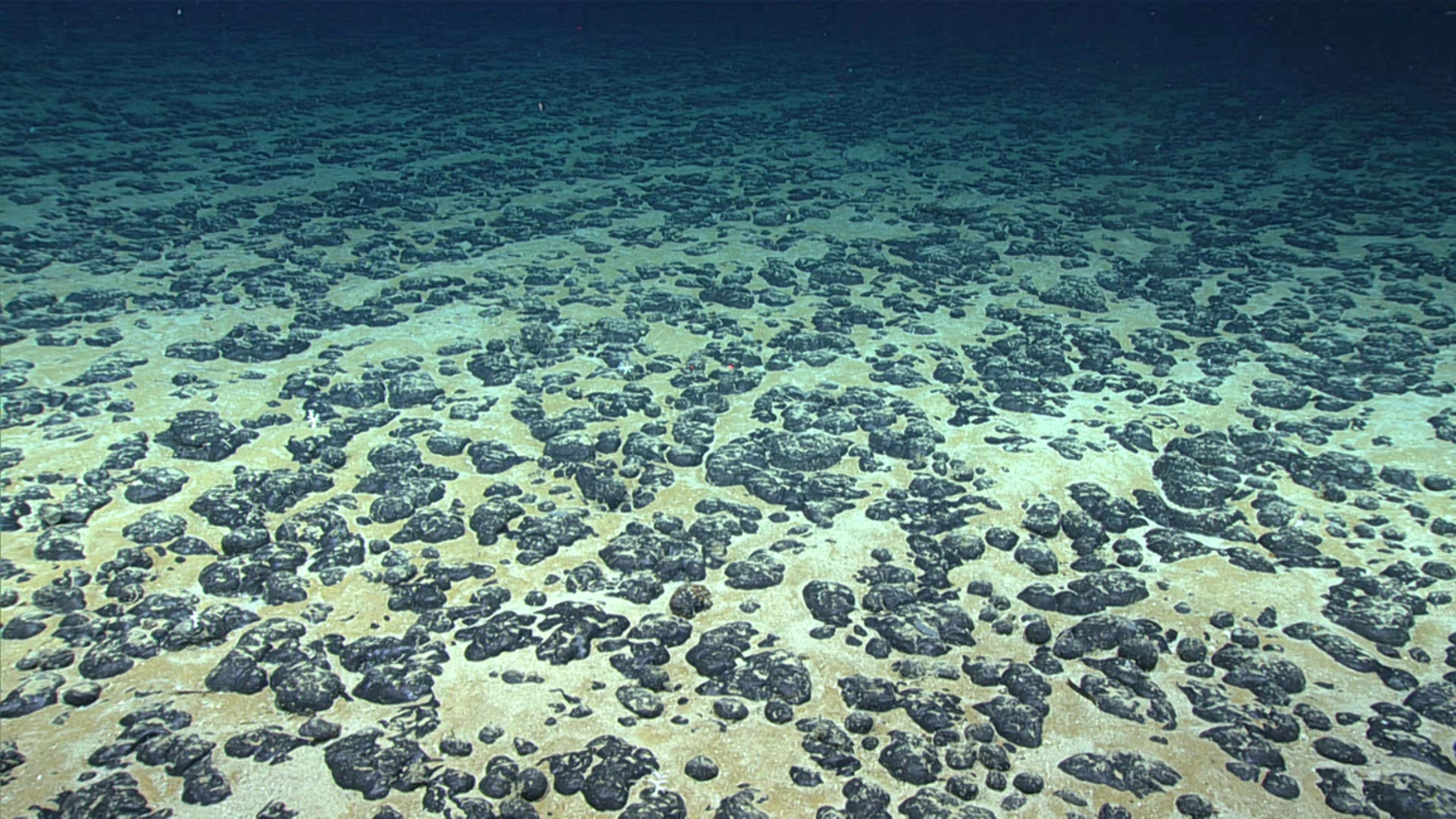

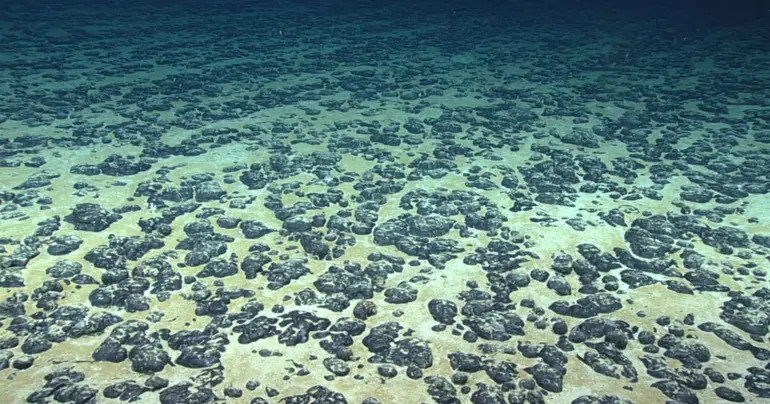

Deep-sea mining in the Pacific, including areas near Samoa, could be detrimental to the environment, according to a research paper prepared by the Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP).

The United States plans a US$20 million seabed survey off American Samoa in 2026 to map critical minerals. The next step would be accessing and extracting them.

Samoa, which is close to American Samoa, could be vulnerable to the environmental impacts of this work.

The paper by SPREP reviews known environmental issues and challenges of deep-sea mining in the region, highlights these risks and urges caution.

The research said extraction of minerals could destroy seabed habitats, threaten rare and unknown species, and create sediment plumes that spread far, while noise, light, pollution, and toxic metals may affect midwater species like tuna. These impacts could damage marine ecosystems, disrupt fisheries that supply half the world’s tuna, and affect the safety of seafood for human consumption.

James Atherton of the Samoa Conservation Society warned that seabed mining in American Samoa could harm Samoa’s marine environment. He criticised the US for rolling back protections on Pacific marine reserves, saying reduced conservation threatens the resilience of marine ecosystems amid climate change, overfishing, and pollution.

Even though several Pacific nations have already received deep-sea mining exploration licenses, research shows that recovery from mining damage could take decades—or may never happen. The DISCOL experiment near Peru, which simulated seabed mining, created sediment plumes that buried marine life and spread farther than expected. Thirty years later, the site still shows fewer species, lower microbial activity, and reduced numbers of suspension feeders.

Past mining in the Pacific shows weak oversight and serious damage. Papua New Guinea, Nauru, Banaba, Palau, and the Solomon Islands have all faced environmental and social problems from land mining.

The World Bank notes that most nations considering deep-sea mining lack experience and urges caution, protecting the ocean, communities, and even considering not mining at all.

“Under these circumstances, there is a need for caution, giving special attention to protecting the marine environment and the people who value it. A sound precautionary approach, which does not preclude the option of ‘no development,’ is needed to avoid or minimize temporary or lasting harm to the environment, to the people, and to the economy,” said the World Bank in a report.

“Deep‐sea mining as an issue is a complex composite of environmental, economic, policy, governance, international, regional and community concerns. On the one hand, DSM offers the prospect of increasing access to relatively scarce mineral resources that can be used to support the development of sustainable energy solutions. On the other hand, it entails high environmental costs and economic risk for countries in the region,” said the SPREP paper

Pacific island countries face a conflict between protecting their oceans and pursuing industrial-scale deep-sea mining. They have committed to international goals like Sustainable Development Target 14.2, which calls for managing and restoring marine ecosystems to keep oceans healthy. Regional values and agreements, including the Paris Agreement, emphasise the importance of preserving ocean integrity and biodiversity while addressing climate change.

The threats and uncertainties of deep‐sea mining, as summarised in the SPREP paper, reinforce the need for SPREP members to apply the precautionary approach adopted by countries in the Rio Declaration in 1992: “In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost‐effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

Deep-sea mining in international waters is risky, and its impacts on the environment, biodiversity, and human activities are not fully known. The EU says mining should wait until risks are understood, technologies are safe, and decision-making is transparent.

SPREP said it supported a 10-year moratorium for Pacific islands to study environmental, social, and economic effects, ensure marine life protection, review the International Seabed Authority, and promote recycling of scarce minerals from sources like discarded phones.

By Andrina Elvira Burkhart

•

04 February 2026, 9:00AM

By Andrina Elvira Burkhart

•

04 February 2026, 9:00AM