Report shows minimum wage increase now past due

By James Robertson

•

09 September 2019, 11:00AM

By James Robertson

•

09 September 2019, 11:00AM

Of all the complex issues currently confronting the Samoan Government none has inspired timidity like minimum wage policy.

The Commerce Minister, Lautafi Fio Purcell, put in plainly this June when he said: “To say that the minimum wage is extra sensitive is an understatement”.

The drumbeat for an increase to the current wage of $2.30 tala (last reviewed in 2015) has been increasingly steadily all year.

In January the Deputy Speaker, Nafo’itoa Talaimanu Keti, called for an increase, albeit a modest one. In March the Samoa First Union said it was upping its request for an increase by more than 50 per cent.

Then in May, the International Monetary Fund - an organisation not generally known to be a hotbed of communist sympathisers - said the Government should raise the rate to $3 tala.

But today’s report in the Samoa Observer showing that research prepared by Australia's aid agency at the request of the Government recommends an increase to $3.70, should be the final sign that this equivocation has gone on too long.

We can understand the Government’s instinct to caution.

Only those with hearts of stone could be unaffected by the fact that so many Samoans are working to earn an hourly salary that does not cover a loaf of bread.

But only a decade ago American Samoa provided a cautionary tale in the ways in which well intentioned wage rises can hurt the very help they intent to help.

In a case that now features in economics textbooks about unintended consequences, the American Congress hiked the minimum wage in the U.S. territory from just over $3 to just over $7.

The effect was ruinous. Major manufacturers pulled out due to higher labour costs and workers lost jobs.

At some point higher wages simply means fewer jobs. Balance is critical.

But the new research makes it clear that the Government has been cautious for too long now – and the poorest Samoans have been paying the price.

The Government’s last wage hike was in 2015 (which was itself delayed for reasons of fiscal caution).

As the recent report shows much has changed in the past five years.

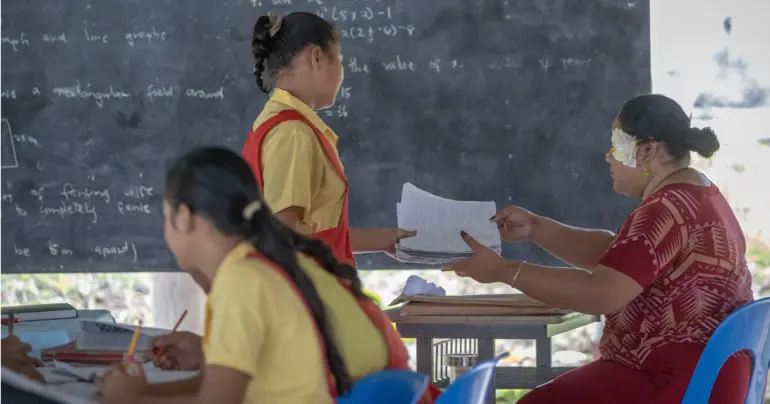

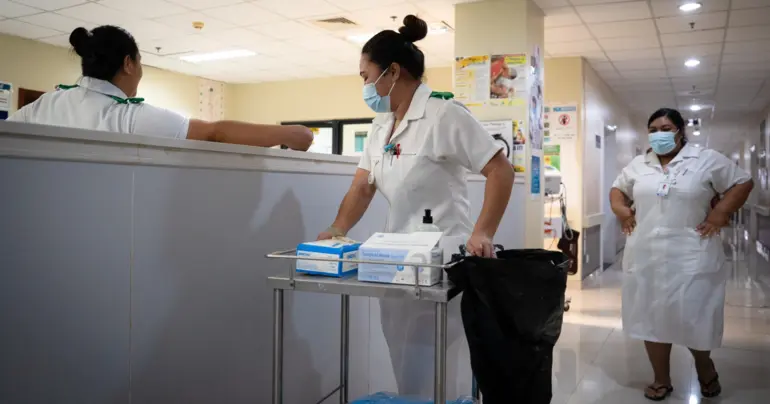

The cost of basic necessities such as food has jumped some 15 per cent in the five years to 2019; transport has increased 12 per cent; and healthcare and education are, similarly, up by more than 15 per cent.

The report’s recommendation for a hike amounting to more than 60 per cent will no doubt make some businesses and employer groups protest. These objections are to be expected but the substance behind them should also be considered.

The figure of $3.7 tala has been arrived at by calculating how much money a worker in the bottom third of Samoa’s economy requires to keep pace with the rising costs of these basic human needs.

At the same time as the worst off have seen their relative incomes fall, the richest tenth of the Samoan workforce has enjoyed an increase in its wages of some 10 per cent.

Samoan’s wages have not only fallen behind the pace of these increases but also the standard of what constitutes a basic living in the Pacific.

The Marshall Islands and Palau have introduced legislation that legally ensures their wages rise progressively; Fiji, the Solomon Islands and Kiribati have all also approved increases.

Samoan workers earning minimum wage are now in the sorry position of being close to the worst compensated in the entire region.

Minimum wages here lag conspicuously behind just about every other country in the Pacific, in many cases by several hundred tala a month.

Much of Samoa remains employed in the ‘informal sector’ and so will not be directly legally affected by a wage change.

But research shows that the number of people employed in formal work in Samoa is rising. These rises are especially rapid amongst younger workers.

Nonetheless the International Labour Organisation has found that minimum wage law rises influences positively the amount of money paid to workers in the informal sector too.

The name given to this theory is the “lighthouse effect”, which is the way in which employers of all kinds respond to a signal about what is a socially acceptable amount of pay.

We believe the Government has for too long been sending the wrong signal.

By James Robertson

•

09 September 2019, 11:00AM

By James Robertson

•

09 September 2019, 11:00AM